Vincent Benavides was the

son of the gaoler of Quirihue in the

district of Conception. He was a man of

ferocious manners, and had been guilty of

several murders. Upon the breaking out of

the revolutionary war, he entered the

patriot army as a private soldier; and was a

serjeant of grenadiers at the time of the

first Chilian revolution. He, however,

deserted to the Spaniards, and was taken

prisoner in their service, when they

sustained, on the plains of Maypo, on the

5th of April, 1818, that defeat which

decided their fortunes in that part of

America, and secured the independence of

Chili. Benavides, his brother, and some

other traitors to the Chilian cause, were

sentenced to death, and brought forth in the

Plaza, or public square of Santiago, in

order to be shot. Benavides, though terribly

wounded by the discharge, was not killed;

but he had the presence of mind to

counterfeit death in so perfect a manner,

that the imposture was not suspected. The

bodies of the traitors were not buried, but

dragged away to a distance, and there left

to be devoured by the gallinazos or

vultures. The serjeant who had the

superintendence of this part of the

ceremony, had a personal hatred to

Benavides, on account of that person having

murdered some of his relations; and, to

gratify his revenge, he drew his sword, and

gave the dead body, (as he thought,) a

severe gash in the side, as they were

dragging it along. The resolute Benavides

had fortitude to bear this also, without

flinching or even showing the least

indication of life; and one cannot help

regretting that so determined a power of

endurance had not been turned to a better

purpose.

Benavides lay like a dead man, in the

heap of carcasses, until it became dark; and

then, pierced with shot, and gashed by the

sword as he was, he crawled to a neighboring

cottage, the inhabitants of which received

him with the greatest kindness, and attended

him with the greatest care.

The daring ruffian, who knew the value of

his own talents and courage, being aware

that General San Martin was planning the

expedition to Peru, a service in which there

would be much of desperation and danger,

sent word to the General that he was alive,

and invited him to a secret conference at

midnight, in the same Plaza in which it was

believed Benavides had been shot. The signal

agreed upon, was, that they should strike

fire three times with their flints, as that

was not likely to be answered by any but the

proper party, and yet was not calculated to

awaken suspicion.

San Martin, alone, and provided with a

brace of pistols, met the desperado; and

after a long conference, it was agreed that

Benavides should, in the mean time, go out

against the Araucan Indians; but that he

should hold himself in readiness to proceed

to Peru, when the expedition suited.

Having procured the requisite passports,

he proceeded to Chili, where, having again

diverted the Chilians, he succeeded in

persuading the commander of the Spanish

troops, that he had force sufficient to

carry on the war against Chili; and the

commander in consequence retired to

Valdivia, and left Benavides commander of

the whole frontier on the Biobio.

Having thus cleared the coast of the

Spanish commander, he went over to the

Araucans, or rather, he formed a band of

armed robbers, who committed every cruelty,

and were guilty of every perfidy in the

south of Chili. Whereever Benavides came,

his footsteps were marked with blood, and

the old men, the women, and the children,

were butchered lest they should give notice

of his motions.

When he had rendered himself formidable

by land, he resolved to be equally powerful

upon the sea. He equipped a corsair, with

instructions to capture the vessels of all

nations; and as Araucan is directly opposite

the island of Santa Maria, where vessels put

in for refreshment, after having doubled

Cape Horn, his situation was well adapted

for his purpose. He was but too successful.

The first of his prizes was the American

ship Hero, which he took by surprise in the

night; the second, was the Herculia, a brig

belonging to the same country. While the

unconscious crew were proceeding, as usual,

to catch seals on this island, lying about

three leagues from the main land of Arauca,

an armed body of men rushed from the woods,

and overpowering them, tied their hands

behind them, and left them under a guard on

the beach. These were no other than the

pirates, who now took the Herculia's own

boats, and going on board, surprised the

captain and four of his crew, who had

remained to take care of the brig; and

having brought off the prisoners from the

beach, threw them all into the hold, closing

the hatches over them. They then tripped the

vessel's anchor, and sailing over in triumph

to Arauca, were received by Benavides, with

a salute of musketry fired under the Spanish

flag, which it was their chief's pleasure to

hoist on that day. In the course of the next

night, Benavides ordered the captain and his

crew to be removed to a house on shore, at

some distance from the town; then taking

them out, one by one, he stripped and

pillaged them of all they possessed,

threatening them the whole time with drawn

swords and loaded muskets. Next morning he

paid the prisoners a visit and ordered them

to the capital, called together the

principal people of the town, and desired

each to select one as a servant. The captain

and four others not happening to please the

fancy of any one, Benavides, after saying he

would himself take charge of the captain,

gave directions, on pain of instant death,

that some one should hold themselves

responsible for the other prisoners. Some

days after this they were called together,

and required to serve as soldiers in the

pirates army; an order to which they

consented, knowing well by what they had

already seen, that the consequence of

refusal would be fatal.

Benavides, though unquestionably a

ferocious savage, was, nevertheless, a man

of resource, full of activity, and of

considerable energy of character. He

converted the whale spears and harpoons into

lances for his cavalry, and halberts for his

sergeants; and out of the sails he made

trowsers for half of his army; the

carpenters he set to work making baggage

carts and repairing his boats; the armourers

he kept perpetually at work, mending

muskets, and making pikes; managing in this

way, to turn the skill of every one of his

prisoners to some useful account. He treated

the officers, too, not unkindly, allowed

them to live in his house, and was very

anxious on all occasions, to have their

advice respecting the equipment of his

troops.

Upon one occasion, when walking with the

captain of the Herculia, he remarked, that

his army was now almost complete in every

respect, except in one essential particular,

and it cut him, he said to the soul, to

think of such a deficiency; he had no

trumpets for his cavalry, and added, that it

was utterly impossible to make the fellows

believe themselves dragoons, unless they

heard a blast in their ears at every turn;

and neither men nor horses would ever do

their duty properly, if not roused to it by

the sound of a trumpet; in short he

declared, some device must be hit upon to

supply this equipment. The captain, willing

to ingratiate himself with the pirate, after

a little reflection, suggested to him, that

trumpets might easily be made of copper

sheets on the bottoms of the vessels he had

taken. "Very true," cried the delighted

chief, "how came I not to think of that

before?" Instantly all hands were employed

in ripping off the copper, and the armourers

being set to work under his personal

superintendence, the whole camp, before

night, resounded with the warlike blasts of

the cavalry.

The captain of the ship, who had given

him the brilliant idea of the copper

trumpets, had by these means, so far won

upon his good will and confidence, as to be

allowed a considerable range to walk on. He

of course, was always looking out for some

plan of escape, and at length an opportunity

occurring, he, with the mate of the Ocean,

and nine of his crew, seized two whale

boats, imprudently left on the banks of the

river, and rowed off. Before quitting the

shore, they took the precaution of staving

all the other boats, to prevent pursuit, and

accordingly, though their escape was

immediately discovered, they succeeded in

getting so much the start of the people whom

Benavides sent in pursuit of them, that they

reached St. Mary's Island in safety. Here

they caught several seals upon which they

subsisted very miserably till they reached

Valparaiso. It was in consequence of their

report of Benavides proceedings made to Sir

Thomas Hardy, the commander-in-chief, that

he deemed it proper to send a ship to rescue

if possible, the remaining unfortunate

captives at Arauca.

Benavides having manned the Herculia, it

suited the mate, (the captain and crew being

detained as hostages,) to sail with the brig

to Chili, and seek aid from the Spanish

governor. The Herculia returned with a

twenty-four pounder, two field-pieces,

eleven Spanish officers, and twenty

soldiers, together with the most flattering

letters and congratulations to the worthy

ally of his Most Catholic Majesty. Soon

after this he captured the Perseverance,

English whaler, and the American brig Ocean,

bound for Lima, with several thousand stand

of arms on board. The captain of the

Herculia, with the mate of the Ocean, and

several men, after suffering great

hardships, landed at Valparaiso, and gave

notice of the proceedings of Benavides; and

in consequence, Sir Thomas Hardy directed

Captain Hall to proceed to Arauca with the

convoy, to set the captives free, if

possible.

It was for the accomplishment of this

service that Capt. Hall sailed from

Valparaiso; and he called at Conception on

his way, in order to glean information

respecting the pirate. Here the Captain

ascertained that Benavides was between two

considerable bodies of Chilian force, on the

Chilian side of the Biobio, and one of those

bodies between him and the river.

Having to wait two days at Conception for

information, Captain Hall occupied them in

observing the place; the country he

describes as green and fertile, and having

none of the dry and desert character of the

environs of Valparaiso. Abundance of

vegetables, wood, and also coals, are found

on the shores of the bay.

On the 12th of October, the captain heard

of the defeat of Benavides, and his flight,

alone, across the Biobio into the Araucan

country; and also that two of the Americans

whom he had taken with him had made their

escape, and were on board the Chacabuco. As

these were the only persons who could give

Captain Hall information respecting the

prisoners of whom he was in quest, he set

out in search of the vessel, and after two

days' search, found her at anchor near the

island of Mocha. From thence he learned that

the captain of the Ocean, with several

English and American seamen had been left at

Arauca, when Benavides went on his

expedition, and he sailed for that place

immediately.

He was too late, however; the Chilian

forces had already made a successful attack,

and the Indians had fled, setting fire to

the town and the ships. The Indians, who

were in league with the Chilians, were every

way as wild as those who arrayed themselves

under Benavides. Capt. Hall, upon his return

to Conception, though dissuaded from it by

the governor, visited the Indian encampment.

When the captain and his associates

entered the courtyard, they observed a party

seated on the ground, round a great tub of

wine, who hailed their entrance with loud

shouts, or rather yells, and boisterously

demanded their business; to all appearance

very little pleased with the interruption.

The interpreter became alarmed, and wished

them to retire; but this the captain thought

imprudent, as each man had his long spear

close at hand, resting against the eaves of

the house. Had they attempted to escape they

must have been taken, and possibly

sacrificed, by these drunken savages. As

their best chance seemed to lie in treating

them without any show of distrust, they

advanced to the circle with a good humored

confidence, which appeased them

considerably. One of the party rose and

embraced them in the Indian fashion, which

they had learned from the gentlemen who had

been prisoners with Benavides. After this

ceremony they roared out to them to sit down

on the ground, and with the most boisterous

hospitality, insisted on their drinking with

them; a request which they cheerfully

complied with. Their anger soon vanished,

and was succeeded by mirth and satisfaction,

which speedily became as outrageous as their

displeasure had been at first. Seizing a

favorable opportunity, Captain Hall stated

his wish to have an interview with their

chief, upon which a message was sent to him;

but he did not think fit to show himself for

a considerable time, during which they

remained with the party round the tub, who

continued swilling their wine like so many

hogs. Their heads soon became affected, and

their obstreperous mirth increasing every

minute, the situation of the strangers

became by no means agreeable.

At length Peneleo's door opened, and the

chief made his appearance; he did not

condescend, however, to cross the threshold,

but leaned against the door post to prevent

falling, being by some degrees more drunk

than any of his people. A more finished

picture of a savage cannot be conceived. He

was a tall, broad shouldered man; with a

prodigiously large head, and a square-shaped

bloated face, from which peeped out two very

small eyes, partly hid by an immense

superfluity of black, coarse, oily, straight

hair, covering his cheeks, hanging over his

shoulders, and rendering his head somewhat

the shape and size of a bee-hive. Over his

shoulders was thrown a poncho of coarse

blanket stuff. He received them very

gruffly, and appeared irritated and sulky at

having been disturbed; he was still more

offended when he learned that they wished to

see his captive. They in vain endeavored to

explain their real views; but he grunted out

his answer in a tone and manner which showed

them plainly that he neither did, nor wished

to understand them.

Whilst in conversation with Peneleo, they

stole an occasional glance at his apartment.

By the side of the fire burning in the

middle of the floor, was seated a young

Indian woman, with long black hair reaching

to the ground; this, they conceived, could

be no other than one of the unfortunate

persons they were in search of; and they

were somewhat disappointed to observe, that

the lady was neither in tears, nor

apparently very miserable; they therefore

came away impressed with the unsentimental

idea, that the amiable Peneleo had already

made some impression on her young heart.

Two Indians, who were not so drunk as the

rest, followed them to the outside of the

court, and told them that several foreigners

had been taken by the Chilians in the battle

near Chilian, and were now safe. The

interpreter hinted to them that this was

probably invented by these cunning people,

on hearing their questions in the court; but

he advised them, as a matter of policy, to

give them each a piece of money, and to get

away as far as they could.

Captain Hall returned to Conception on

the 23d of October, reached Valparaiso on

the 26th, and in two weeks thereafter, the

men of whom he was in search, made their

appearance.

The bloody career of Benavides now drew

near to a close. The defeat on the Chilian

side of the Biobio, and the burning of

Arauca with the loss of his vessels, he

never recovered. At length, in the end of

December 1821, discovering the miserable

state to which he was reduced, he entreated

the Intendant of Conception, that he might

be received on giving himself up along with

his partisans. This generous chief accepted

his offer, and informed the supreme

government; but in the meantime Benavides

embarked in a launch, at the mouth of the

river Lebo, and fled, with the intention of

joining a division of the enemy's army,

which he supposed to be at some one of the

ports on the south coast of Peru. It was

indeed absurd to expect any good faith from

such an intriguer; for in his letters at

this time, he offered his services to Chili

and promised fidelity, while his real

intention was still to follow the enemy. He

finally left the unhappy province of

Conception, the theatre of so many miserable

scenes, overwhelmed with the misery which he

had caused, without ever recollecting that

it was in that province that he had first

drawn his breath.

His despair in the boat made his conduct

insupportable to those who accompanied him,

and they rejoiced when they were obliged to

put into the harbor of Topocalma in search

of water of which they had run short. He was

now arrested by some patriotic individuals.

From the notorious nature of his crimes,

alone, even the most impartial stranger

would have condemned him to the last

punishment; but the supreme government

wished to hear what he had to say for

himself, and ordered him to be tried

according to the laws. It appearing on his

trial that he had placed himself beyond the

laws of society, such punishment was awarded

him as any one of his crimes deserved. As a

pirate, he merited death, and as a destroyer

of whole towns, it became necessary to put

him to death in such a manner as might

satisfy outraged humanity, and terrify

others who should dare to imitate him. In

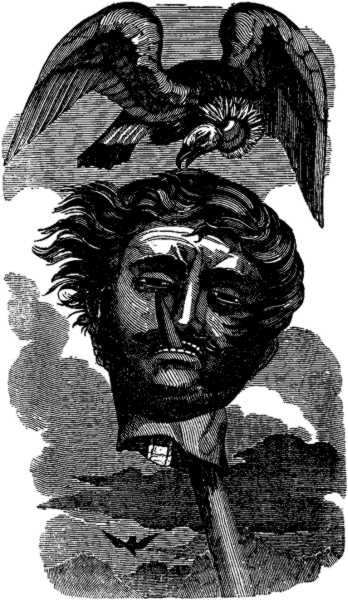

pursuance of the sentence passed upon him,

he was dragged from the prison in a pannier

tied to the tail of a mule, and was hanged

in the great square; his head and hands were

afterwards cut off, in order to their being

placed upon high poles, to point out the

places of his horrid crimes, Santa Juona,

Tarpellanca and Arauca.

The head of Benavides stuck on a

pole.

|